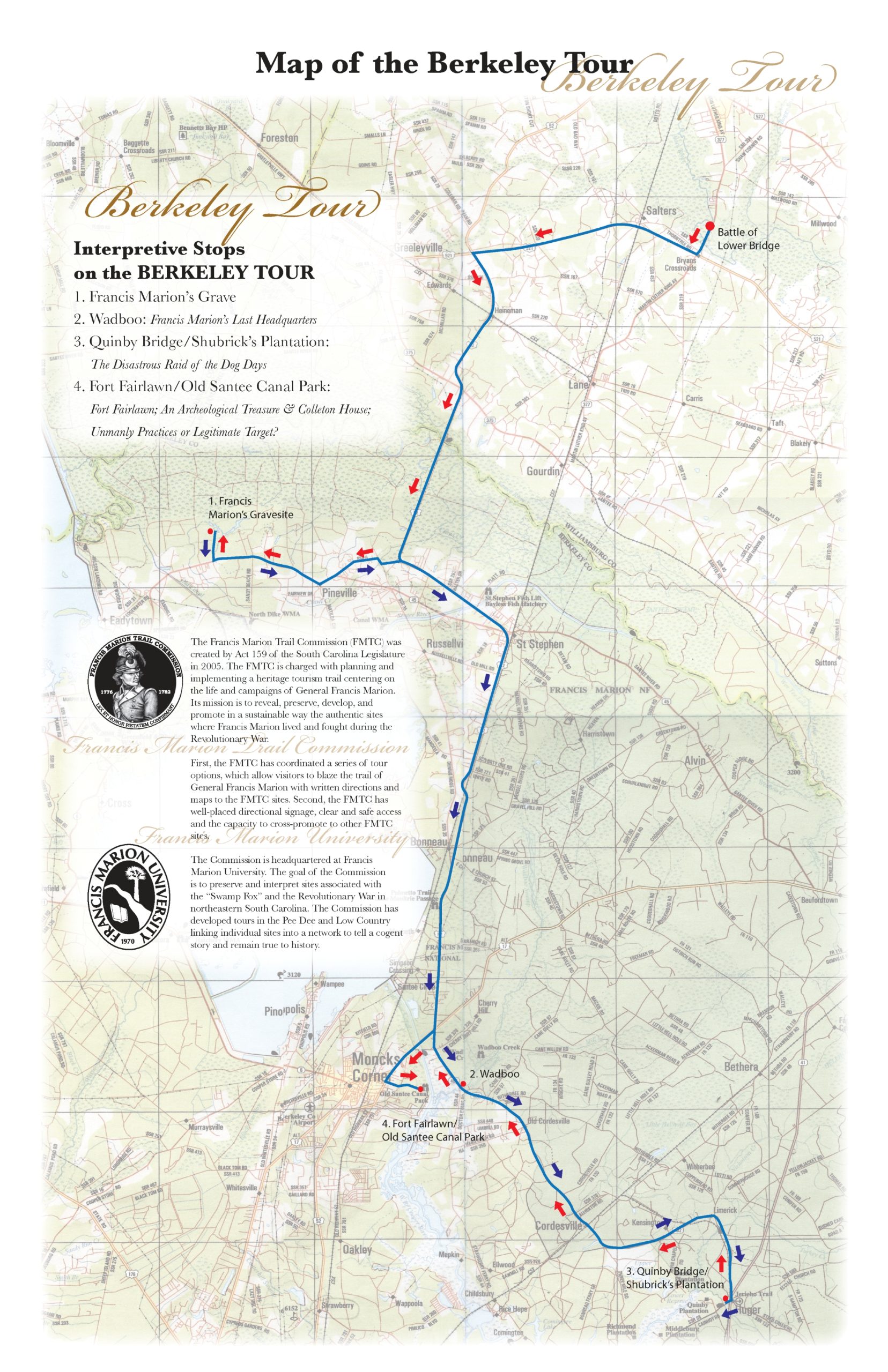

Berkeley Tour

Of the four sites in Berkeley County, three are associated with controversial episodes in Francis Marion’s career: Quinby Bridge, where he vowed never again to work with Gen. Thomas Sumter, another Patriot militia leader; and Colleton House and Fort Fairlawn, where Marion’s men were accused of violating the rules of war. Also, here is Wadboo Barony, site of Marion’s last encampment of the war. Along the way, be sure to stop at the Train Depot visitor center and gift shop in historic Moncks Corner; visit the church and gardens of Mepkin Abbey, a Trappist monastery; and check out the many outdoor recreational activities in the Francis Marion National Forest.

STOP 1: Francis Marion’s Grave

Driving Directions:

Beginning at the historical marker and interpretive sign at Lower Bridge on Hwy. 377, go .5 mile and turn right onto Hwy. 521. Go several miles to the intersection with Hwy. 52 and turn left onto Hwy. 52. Continue on Hwy. 52 for about 10.5 miles over a long causeway over the Santee River and swamp until you come to a sharp left hand curve in Hwy. 52. Exit Hwy. 52 to the right onto Col. Maham Drive toward Pineville. There will also be a marker identifying this road as the way to Marion’s Grave. Follow this road through Pineville and beyond for approximately 7 miles until you come to the marked entrance to Marion’s gravesite on the right side of the road (which is now called Hwy. 45). Turn right on the road to Marion’s gravesite and travel 1 mile to the gravesite.

Soldiers in Another War Visit Marion’s Grave

On the 17th day of February, 1865, the day that Sherman burnt Columbia, SC, the Fifth Georgia Regiment was on its march from a point on the South Carolina railroad across the country to the Santee River, moving toward Cheraw. On that march, the regiment passed Belle Isle, St. John’s Parish, where repose the remains of Gen. Francis Marion.

Before they reached that place notice was sent down the line that they were nearing the grave of Marion, and at once a widespread interest on anticipation pervaded the regiment. When they reached Belle Isle, numbers of the soldiers gathered round the rest place of “The Swamp Fox” of the revolution, and gave evidence of an intense feeling of mind and heart, as they looked upon the grave of one who did so much for his country in the days that tried men’s souls. The regimental band played a dirge at the grave which heightened the effect. The marble slab which covers his remains bears the following inscription: “Sacred to the memory of Brigadier General Francis Marion, who departed this life on the 19th of February 1795, in the 63rd year of his age, deeply regretted by all his fellow citizens. History will record his worth, and rising generations embalm his memory as one of the most distinguished patriots of the American Revolution, which elevated his native country to honor and independence, and secured to her the blessing of liberty and peace. This tribute of veneration and gratitude is erected in commemoration of the noble and disinterested virtues of the citizen and the gallant exploits of the soldier, who lived without fear and died without reproach.”

A distinguished historian, speaking of the last days of this patriot, says this: “as of the future he entertained no doubt, so of that awful transition through the valley and shadow of death, he had no fear. ‘Death may be to others,’ said he, ‘a leap in the dark, but I rather consider it a resting place where old age may throw off its burdens.’” His last words were these: “Thank God, I can lay my hand on my heart and say that since I came to man’s estate I have never intentionally done wrong to any.” Thus died Francis Marion, one of the noblest models of the citizen soldier that the world has ever produced. Brave without rashness, prudent without timidity, firm without arrogance, resolved without rudeness, good without cant and virtuous without presumption.[1]

[1] Entire account, including quoted spoken material gathered from “Gen. Francis Marion A Reminiscence of the War of

1861 in the Lower Portion of South Carolina” printed in the Macon Weekly Telegraph of Macon, Georgia, on

27 March 1890.

STOP 2: Wadboo

Driving Directions:

Retrace your route back to Hwy. 52, turn right and proceed 17.9 miles through St. Stephen to Moncks Corner. Coming into Moncks Corner, at the intersection just before you go over the high bridge over the Tail Race Canal, turn left onto Hwy. 402. After a few hundred yards, take a right turn which will allow you to stay on Hwy. 402. Continue about 1.5 miles until you see a large parking lot and boat landing to your left. Turn into this parking lot and near the boat ramp you will see an interpretive sign for Wadboo.

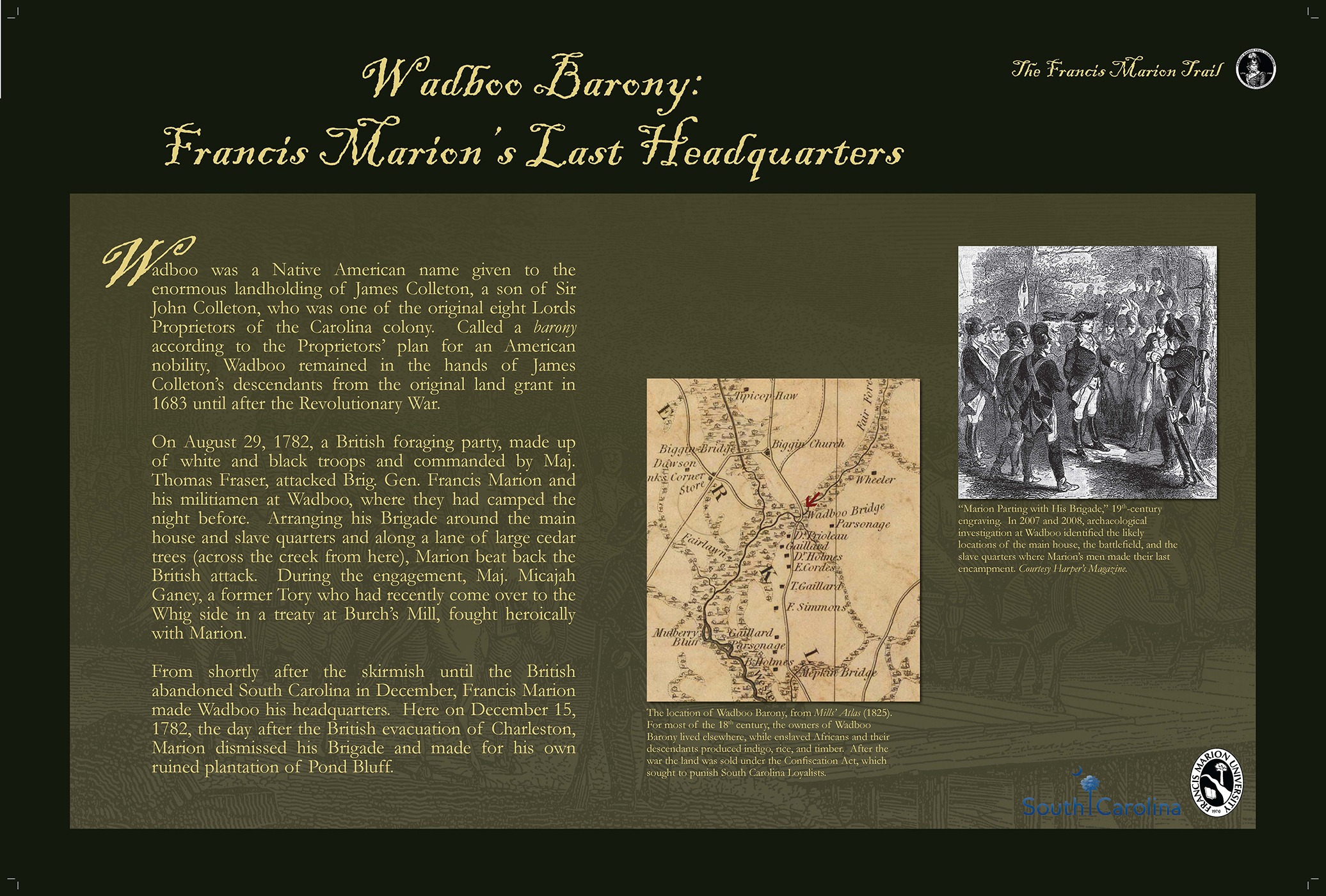

Ambush at Wadboo

In keeping with the tradition of the remarkable battles that punctuated Francis Marion’s military career, the story of his last foray onto the field of battle is a splendid one. Marion managed to maintain his militia even though they were dwindling in numbers and those that stayed exhibited disobedience and a general lack of cooperation. In fact, the ever decreasing numbers prompted him to consolidate Maham’s regiment into the cavalry commanded by James Conyers, under the latter’s direction. With the idea of setting up camp and sending out a foraging party, Marion and his troops traveled to Wadboo Plantation.

The plantation had a history of playing host to foraging visits from both British and American parties. On August 29, 1782 it was Marion’s turn to occupy the mansion while his men were encamped in the out buildings. A foraging party had been sent six miles away; consequently, when news of an approaching British attack led by Major Thomas Fraser was received, Marion found himself without cavalry support. Frazier had first set out to surprise the guards at Biggin Bridge and at Strawberry Ferry. With this serious turn of events Marion quickly called in pickets posted to provide early warning of attack, positioned his men with muskets and rifles behind the cover of cedars lining the approach to the mansion house, and organized a mounted reconnaissance party under Gavin Witherspoon to ride toward the enemy coming from the direction of Wadboo Bridge. The long, hanging branches of the cedars provided excellent cover for the men with muskets and rifles as they waited behind the cedars to ambush Major Fraser and the British.

Witherspoon and his horsemen met the British in the woods near Wadboo Bridge and immediately wheeled about and headed at full gallop for the avenue of cedars leading to the plantation house. He led the British dragoons through an open field and into the avenue of trees, a ploy used by Marion in other successful ambushes. As soon as the Patriot patrol flashed by the hidden men, Witherspoon turned to the left and fell back as if to cover the retreat. A dragoon charged at Witherspoon to cut him down with his sword, but the big man with the quirky grin raised his carbine as the dragoon rose in his stirrups to strike the blow. Witherspoon fired and the dragoon fell from his saddle. Having the advantages of surprise and a thirty-yard target distance, Marion’s militia engaged the British in a shattering volley from muskets loaded with buckshot and with rifle fire.[1] Sixteen dragoons were wounded, four were killed, and the British lost ten horses. However, at the sound of the gunfire the horses pulling Marion’s ammunition wagon bolted and the British captured the wagon in spite of Patriot efforts to recover it. Fraser rallied the British and spent the next hour and a half, just out of range watching the Patriots from a field, but elected not to reengage them.

Marion suffered three officers and eight men wounded, but the most militarily significant loss was the ammunition wagon. Because of the shortage of ammunition Marion ordered a retreat to Santee. Micajah Ganey and his ex-Tories had fought valiantly on the side of the Patriots. The same could not be said, however, for some of the former Loyalists, whose fervor waned when the battle grew too heated. Even so, the battle had been a Patriot victory.

The call to fire on the British dragoons at Wadboo would be the last time Marion issued an order on the field of battle. Of the skirmish, Greene would state; “I wish the militia in every part of the state was equally deserving the same applause.”[2] Edward Rutledge, a member of the Jacksonborough Assembly (and brother to Governor John Rutledge) added his own praise when he quipped; “old Marion has foiled the enemy of late in a very handsome manner.”[3]

[1] Rankin, Hugh F. Francis Marion: The Swamp Fox. Thomas Y. Crowell Company. New York. 1973. Pg. 286

[2] Ibid. Pg. 287

[3] Ibid.

STOP 3: Quinby Bridge | Shubrick’s Plantation

Driving Directions:

Make a left turn out of the parking lot at Wadboo, and proceed down Hwy. 402 for about 14.1 miles to Huger, and at the stop sign turn right onto Hwy. 41. After a short distance turn right onto Cainhoy Road. About 200 yards down this road you will see another parking lot and boat ramp on your right before a small bridge. Turn right into the parking lot and you will see an interpretive sign for the fights at Quinby Creek/Shubrick’s Plantation near the boat ramp.

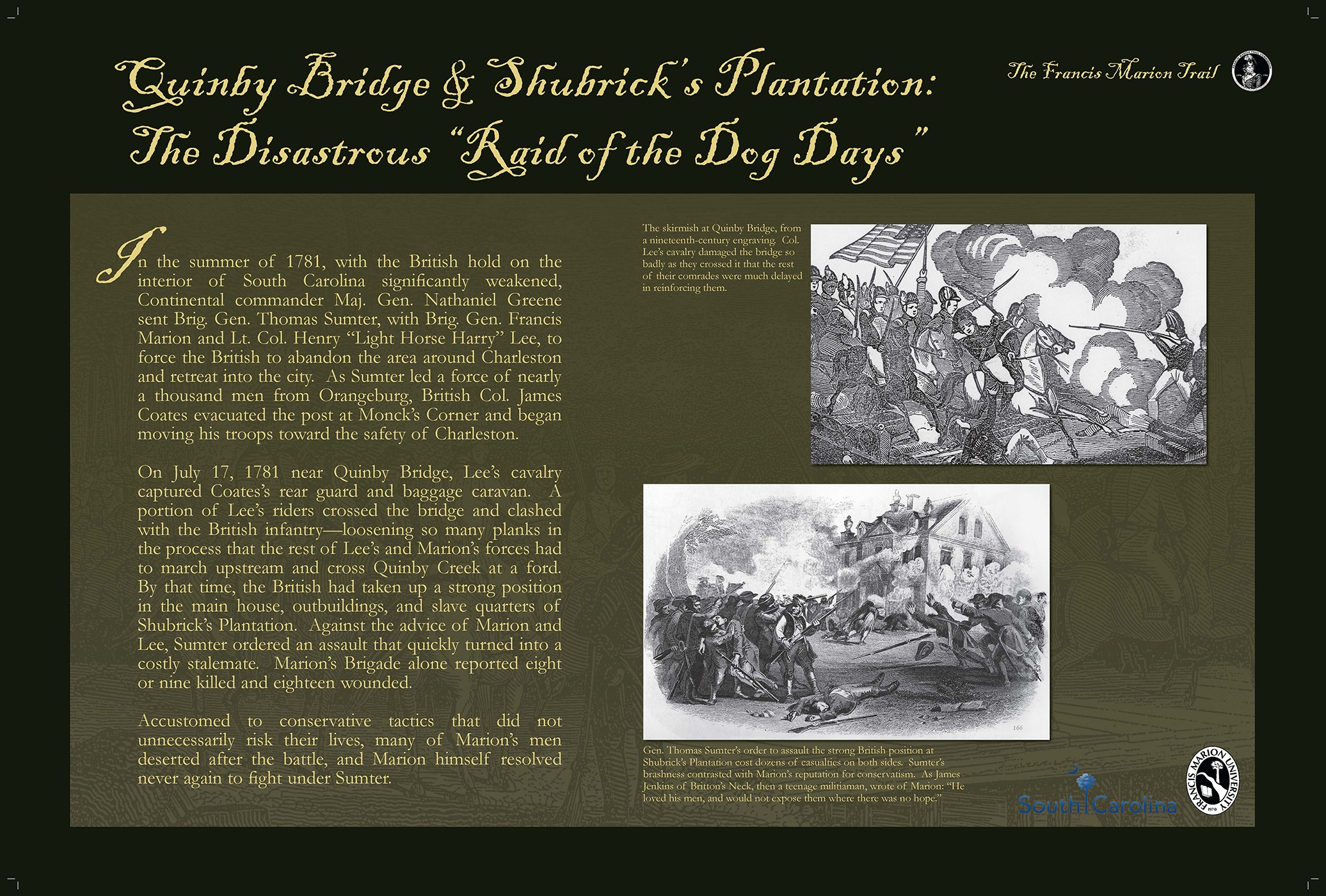

The Disastrous “Raid of the Dog Days”

In the summer of 1781, with the British hold of the interior of South Carolina significantly weakened, Continental commander Gen. Nathaniel Greene sent Gen. Thomas Sumter, Brig. Gen. Francis Marion, and Col. Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee of Virginia to force the British to abandon their posts around Charleston and retreat into the city. As Gen. Sumter led the force of nearly a thousand men from Orangeburg, British Col. James Coates abandoned Monck’s Corner and began moving his troops toward the safety of Charleston.

Near Quinby Bridge, Col. Lee’s cavalry captured Coates’s rear guard and baggage caravan. A portion of Lee’s riders crossed the bridge and clashed with the British infantry—loosening so many planks in the process that the rest of Lee’s and Marion’s forces had to march upstream and cross Quinby Creek at a ford. By that time, the British had taken up a strong position in the main house, outbuildings, and slave quarters of Shubrick’s Plantation. Against the advice of Marion and Lee, Sumter ordered an assault that quickly turned into a costly stalemate. Marion’s Brigade alone reported eight or nine killed and eighteen wounded.

Used to conservative tactics that did not unnecessarily risk their lives, many of Marion’s men deserted after the battle, and Marion himself resolved never again to fight under Sumter.

- The skirmish at Quinby Bridge, from a nineteenth-century engraving. Lee’s cavalry damaged the bridge so badly as they crossed it that the rest of their comrades were much delayed in reinforcing them.

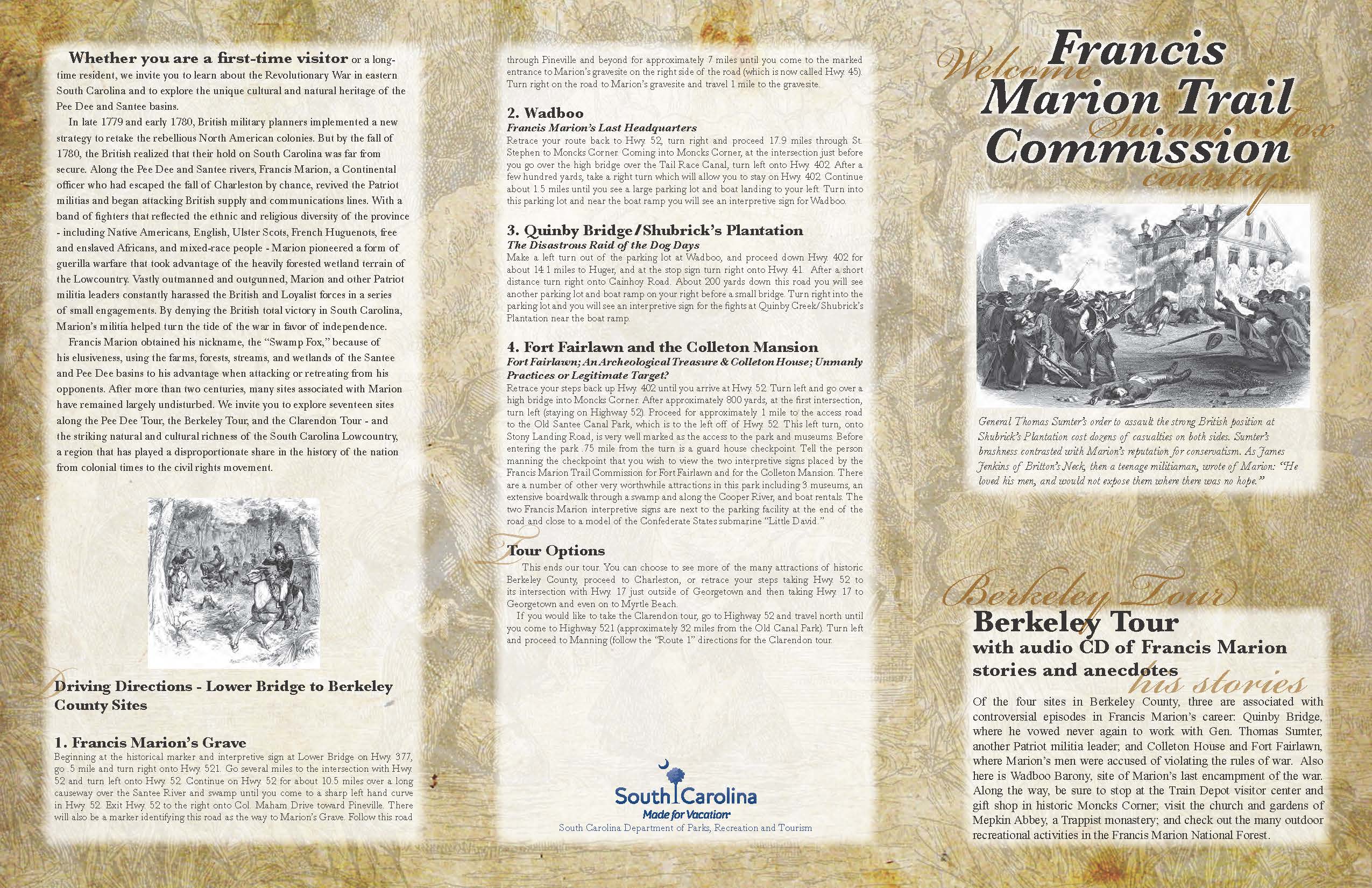

- Thomas Sumter’s order to assault the strong British position at Shubrick’s Plantation cost dozens of casualties on both sides. Sumter’s brashness contrasted with Marion’s reputation for conservatism. As James Jenkins of Britton’s Neck, then a teenage militiaman, wrote of Marion: “He loved his men, and would not expose them where there was no hope.”

STOP 4: Fort Fairlawn and the Colleton Mansion

Driving Directions:

Retrace your steps back up Hwy. 402 until you arrive at Hwy. 52. Turn left and go over a high bridge into Moncks Corner. After approximately 800 yards, at the first intersection, turn left (staying on Highway 52). Proceed for approximately 1 mile to the access road to the Old Santee Canal Park, which is to the left off of Hwy. 52. This left turn, onto Stony Landing Road, is very well marked as the access to the park and museums. Before entering the park .75 mile from the turn is a guard house checkpoint. Tell the person manning the checkpoint that you wish to view the two interpretive signs placed by the Francis Marion Trail Commission for Fort Fairlawn and for the Colleton Mansion. There are a number of other very worthwhile attractions in this park including 3 museums, an extensive boardwalk through a swamp and along the Cooper River, and boat rentals. The two Francis Marion interpretive signs are next to the parking facility at the end of the road and close to a model of the Confederate States submarine “Little David.”

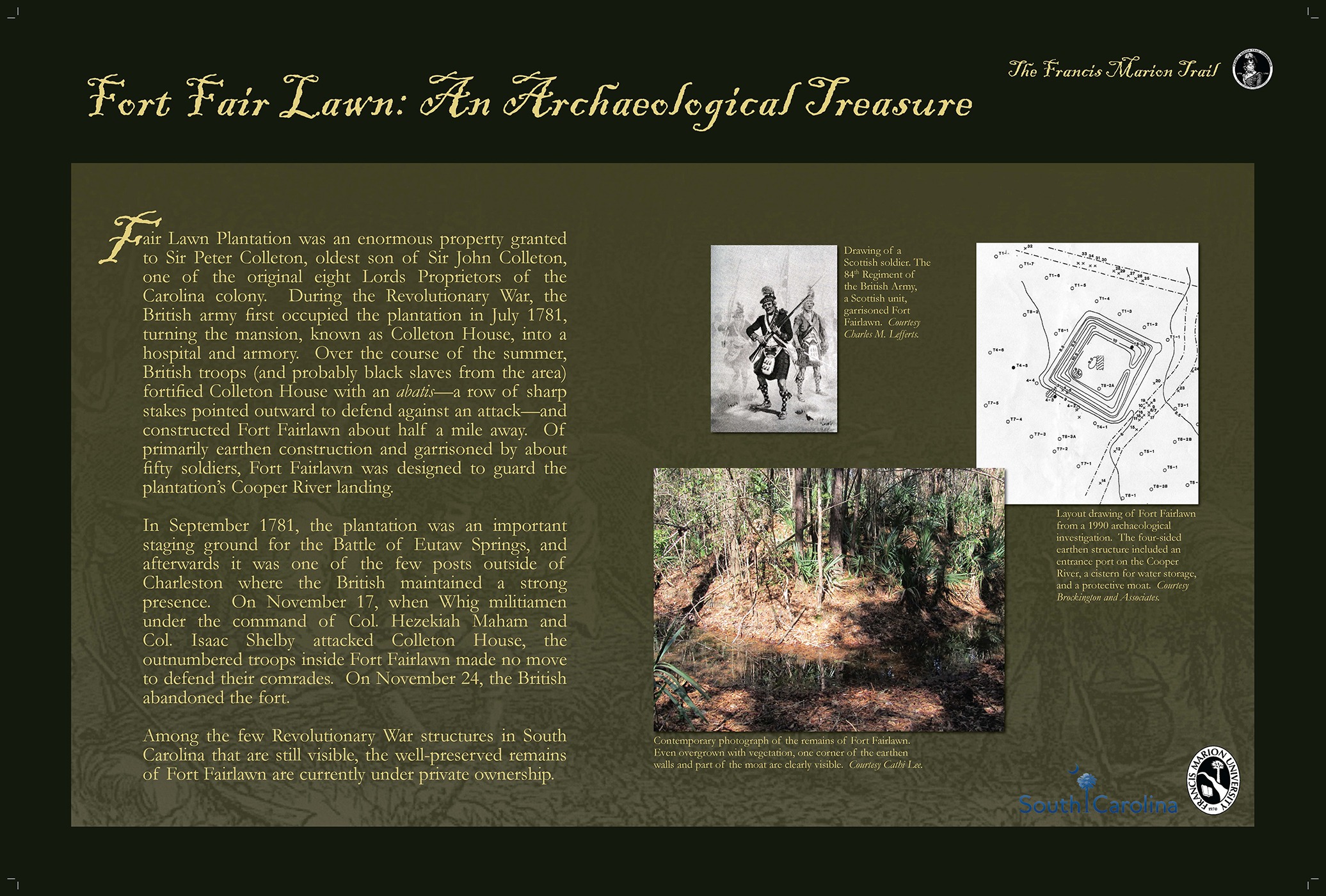

Fort Fairlawn; An Archeological Treasure & Colleton House; Unmanly practices or Legitimate Target?

In November of 1781, Patriot forces in South Carolina received word of George Washington’s victory over Cornwallis at Yorktown. This meant that the British had suffered a devastating blow and it also meant that significant numbers of American reinforcements could be sent to South Carolina to assist Francis Marion, Nathanael Greene, and other Patriot commanders. In October, a force of six hundred over-the-mountain troops, led by Colonels Isaac Shelby and John Sevier had come into South Carolina. Many of these fighters had participated in the great Patriot victory at King’s Mountain. General Greene assigned these men to assist Francis Marion. The one significant action in which these troops worked with Marion’s militia was at the British posts near the Cooper River. One post was a redoubt called Fort Fairlawn and the other was the Colleton Mansion, located about a half mile from the fort. Fort Fairlawn was being used by the British to protect their landing on the Cooper River, and the Colleton Mansion was being used as a hospital for troops afflicted with fever and as a supply depot. Marion assigned two hundred militia under the command of Hezekiah Maham and Isaac Shelby to attack the British at these posts. The fort on the Cooper River was garrisoned by fifty British troops under Captain McLean. Intelligence reports indicated that the number of troops assigned to these posts had been recently reduced.

Maham and Shelby, with their two hundred troops, arrived at the redoubt guarding the Cooper River landing early on November 17. The fort, which still exists today, was square in shape, and surrounded by a small moat with a cistern inside. The British garrison had abandoned their camps outside the redoubt walls and were inside waiting and ready for battle with the much larger Patriot force. Maham and Shelby decided that attacking the strongly defended fort, even with superior numbers, would be a needless waste of Patriot lives. The British knew that the fort provided them with a strategic advantage as long as they stayed inside the walls, but they also realized that they could not leave the safety of the fort to defend the Colleton Mansion without the prospect of certain defeat. Maham and Shelby decided to attack the weakly defended hospital and supply depot located at the Colleton Mansion.

The British inside the Colleton Mansion house and adjacent buildings were offered the chance to surrender. The alternative was that Shelby’s fierce mountaineers would storm the mansion and hack the British to pieces with their tomahawks. McLean’s British soldiers garrisoning the fort made no attempt to intercede. Those inside the Colleton Mansion elected to surrender. Roughly one hundred and fifty British soldiers, together with their doctors and officers, surrendered to Marion’s two commanders. About eighty of the prisoners were physically strong enough to make the march to Marion’s camp; the remaining prisoners were deemed too weak to survive the march and were granted parole after they swore not to participate in any further actions against the Patriots. The house, along with the outbuildings and all the supplies, was set ablaze. Had the house survived until the present, it would have been one of the great historical treasures of South Carolina.

Controversy still surrounds the burning of the Colleton Mansion. Colonel Maham denied setting the fires. General Nathanael Greene, commander of the Patriot troops in the Southern Campaign, claimed that Maham burned the mansion to destroy the British military stores, which the Patriot troops had no means of transporting to their camp. According to General William Moultrie, Maham burned the house because the Patriots were rapidly consuming the British liquor supplies. Colonel Isaac Shelby said that the house was burned immediately after the Patriots left but that it was the British who abandoned it and burned it themselves. Maham and Shelby were the two last men to leave the house and according to Shelby, there was no indication of fire or smoke when they left the building. At a British court of inquiry, the senior British surgeon on duty testified that the house was on fire within twenty minutes after Maham and Shelby arrived on the property. The owner, Louisa Carolina Colleton, recorded a description of the property as she observed it after hostilities ceased and blamed the British for its destruction. Louisa Colleton’s description said that not only the mansion, but also all buildings on the property, were destroyed, including outbuildings, granaries, mills, and a small town.

The action at Fort Fairlawn and Colleton Mansion illustrates that Francis Marion’s commanders, Maham and Shelby, were careful not to squander the lives of the troops under their command and were primarily interested in depriving the British of the means of sustaining themselves. It may be reasonable to conclude that at that point in the war the Patriots felt that they had, for practical purposes, defeated the British. The primary Patriot objective was to encourage the British to leave South Carolina. Inflicting heavy British casualties would have cost Patriot lives and was not therefore the focus of Marion’s forces at this time in the war. Marion is quoted later as saying that he was even willing to send his troops to protect the British while they made preparations to depart if this protection would speed their leaving. Perhaps this isolated incident provides insight into the mind of one of America’s greatest military commanders and a lesson for the future.[1]

[1] Account drawn from the writings of William Dobein James in his A Sketch of the Life of Brig. Gen.

Francis Marion and A History of His Brigade, originally published by Gould and Riley of

Charleston in 1821, and the writings of Terry Lipscomb in his South Carolina Revolutionary

War Battles, published by The South Carolina Department of Archives and History.