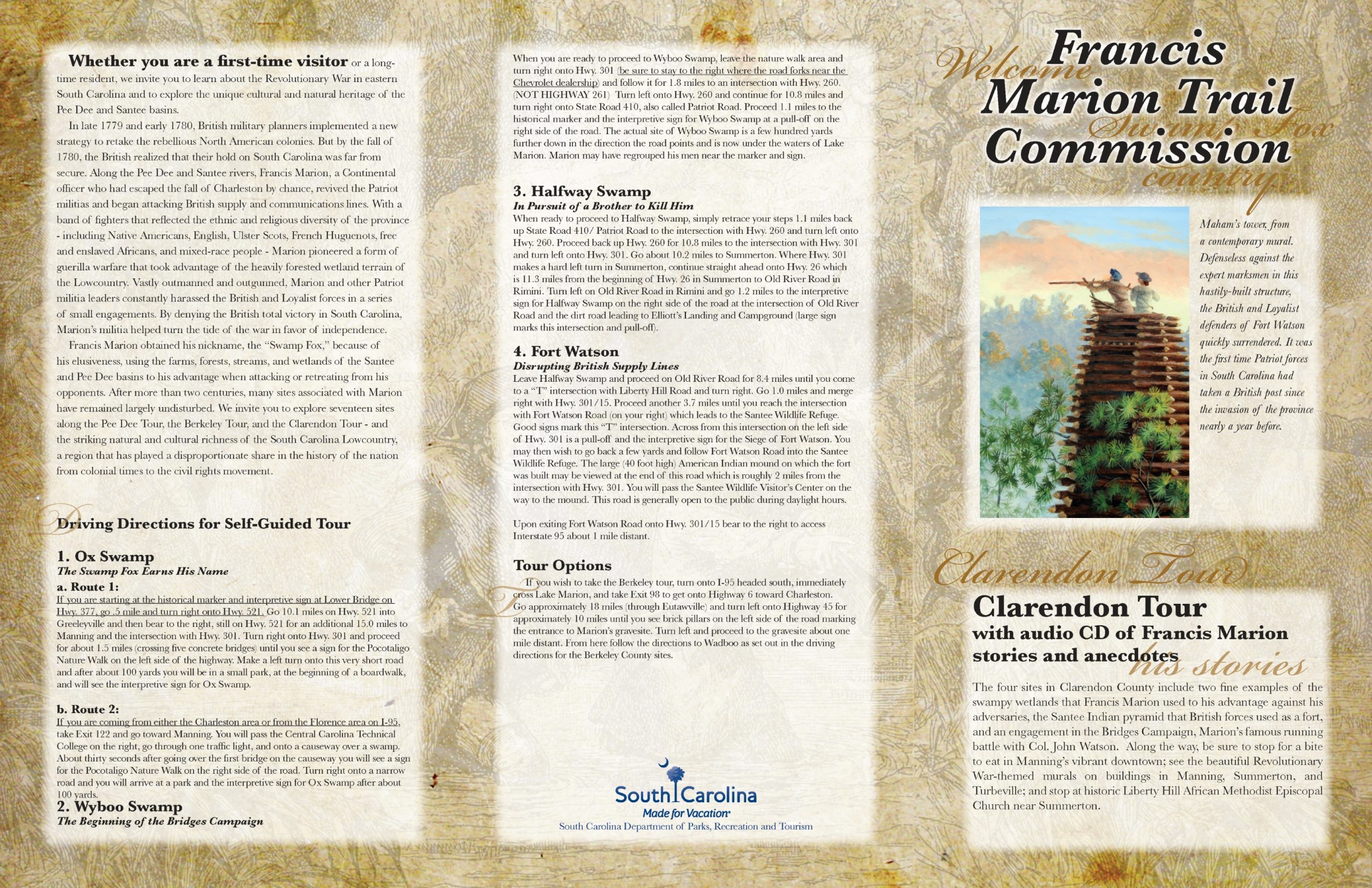

Clarendon Tour

The four sites in Clarendon County include two fine examples of the swampy wetlands that Francis Marion used to his advantage against his adversaries, the Santee Indian pyramid that British forces used as a fort, and an engagement in the Bridges Campaign, Marion’s famous running battle with Col. John Watson. Along the way, be sure to stop for a bite to eat in Manning’s vibrant downtown; see the beautiful Revolutionary War-themed murals on buildings in Manning, Summerton, and Turbeville; and stop at historic Liberty Hill African Methodist Episcopal Church near Summerton.

STOP 1: Ox Swamp

Driving Directions:

Route 1:

If you are starting at the historical marker and interpretive sign at Lower Bridge on Hwy. 377, go .5 mile and turn right onto Hwy. 521. Go 10.1 miles on Hwy. 521 into Greeleyville and then bear to the right, still on Hwy. 521 for an additional 15.0 miles to Manning and the intersection with Hwy. 301. Turn right onto Hwy. 301 and proceed for about 1.5 miles (crossing five concrete bridges) until you see a sign for the Pocotaligo Nature Walk on the left side of the highway. Make a left turn onto this very short road and after about 100 yards you will be in a small park, at the beginning of a boardwalk, and will see the interpretive sign for Ox Swamp.

Route 2:

If you are coming from either the Charleston area or from the Florence area on I-95, take Exit 122 and go toward Manning. You will pass the Central Carolina Technical College on the right, go through one traffic light, and onto a causeway over a swamp. About thirty seconds after going over the first bridge on the causeway you will see a sign for the Pocotaligo Nature Walk on the right side of the road. Turn right onto a narrow road and you will arrive at a park and the interpretive sign for Ox Swamp after about 100 yards.

The Swamp Fox Earns His Name

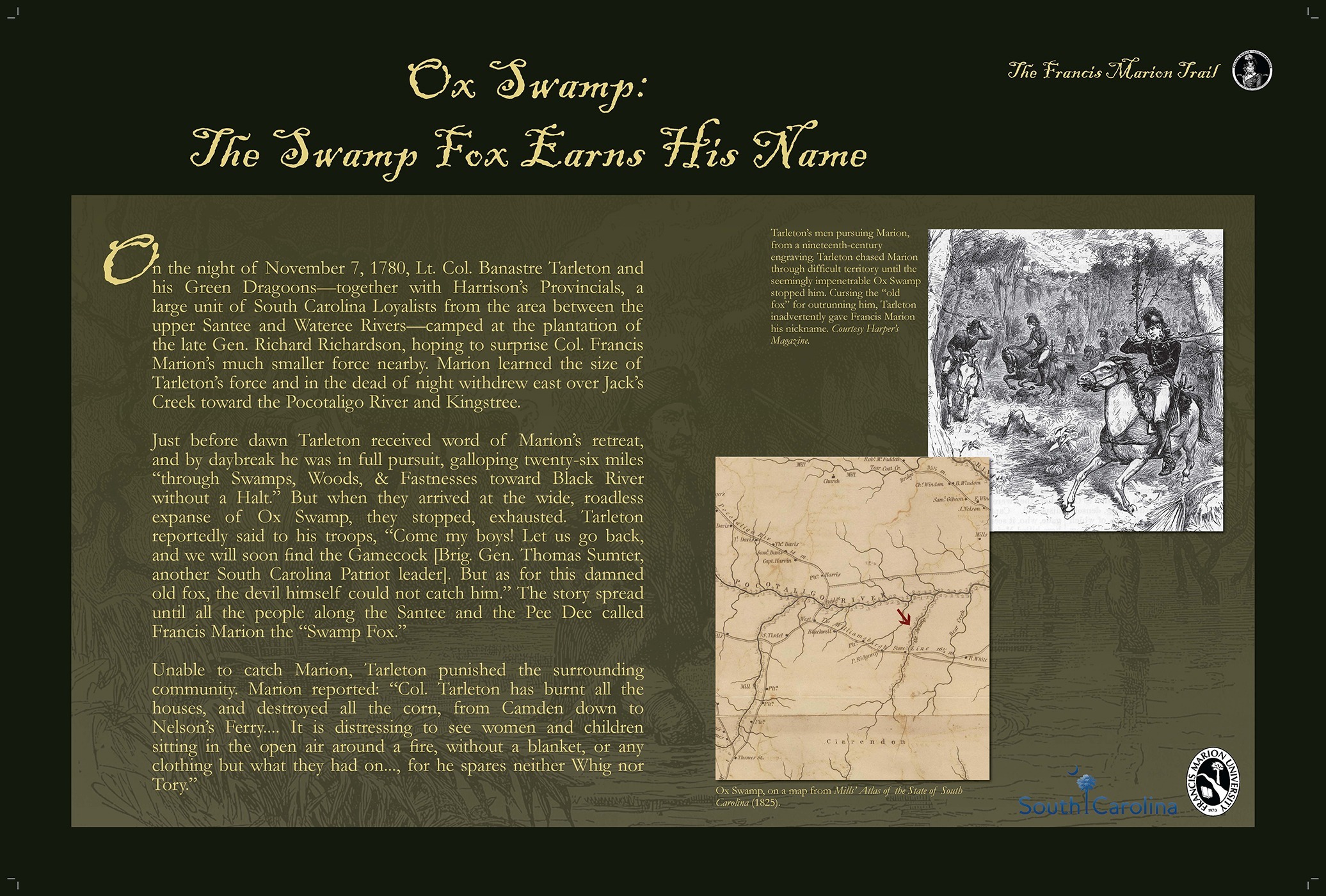

On the night of November 7, 1780, Lt. Colonel Banastre Tarleton and his Green Dragoons – together with Harrison’s Provincials, a large unit of Tories from the area between the upper Santee and Wateree Rivers – camped at the plantation of the late General Richard Richardson, hoping to surprise Francis Marion’s much smaller force.

Marion learned the size of Tarleton’s force and in the dead of night withdrew east over Jack’s Creek toward the Pocotaligo River and Kingstree.

Just before dawn Tarleton received word of Marion’s move and by daybreak was in full pursuit, galloping twenty-six miles “through Swamps, Woods, and Fastness toward Black River without a Halt.” But when they arrived at the wide, roadless expanse of Ox Swamp, they stopped, exhausted. Tarleton reportedly said to his troops, “Come my boys! Let us go back, and we will soon find the Gamecock (General Thomas Sumter, another Patriot partisan leader). But as for this damned old fox, the devil himself could not catch him.” The story spread until all the people along the Santee and the Pee Dee called Francis Marion the “Swamp Fox.” Marion had an ambuscade set for Tarleton at Benbow’s Ferry ten miles east of Ox Swamp on the Black River.

Unable to catch Marion, Tarleton punished the surrounding community. Marion reported: “Col. Tarleton has burnt all the houses, and destroyed all the corn, from Camden down to Nelson’s Ferry… It is distressing to see women and children sitting in the open air around a fire, without a blanket, or any clothing but what they had on …, for he spares neither Whig nor Tory.”

STOP 2: Wyboo Swamp

Driving Directions:

When you are ready to proceed to Wyboo Swamp, leave the nature walk area and turn right onto Hwy. 301 (be sure to stay to the right where the road forks near the Chevrolet dealership) and follow it for 1.8 miles to an intersection with Hwy. 260. (NOT HIGHWAY 261) Turn left onto Hwy. 260 and continue for 10.8 miles and turn right onto State Road 410, also called Patriot Road. Proceed 1.1 miles to the historical marker and the interpretive sign for Wyboo Swamp at a pull-off on the right side of the road. The actual site of Wyboo Swamp is a few hundred yards further down in the direction the road points and is now under the waters of Lake Marion. Marion may have regrouped his men near the marker and sign.

The Beginning of the Bridges Campaign

Marion’s Bridges Campaign was an example of guerilla warfare conducted against a numerically superior and better equipped force trained to fight in the European style of the time. As a Continental officer Marion was trained in the pitched battle European style of fighting – lining up masses of troops facing each other and firing at close range. He was also expert and experienced in guerilla warfare from encounters with the Cherokee many years earlier. Marion’s backwoodsmen were greatly outnumbered, had no cannon, and were poorly equipped and clothed compared to the British and Tories. The militia of the Swamp Fox was, however very mobile thanks to their fast horses, were expert in moving through woods and swamps, and many were armed with a new invention, the rifle. Rifles fired a single relatively small projectile as compared to the larger projectile or multiple shot of muskets with bayonets. Rifles, however, in the expert hands of some of Marion’s militia, were accurate at far greater distances than muskets and would soon terrorize the army of the world’s greatest military power.

At the beginning of March, 1781, the British and Lord Rawdon in Camden were satisfied that Gen. Thomas Sumter was out of picture after being chased off to the Waxhaws. Now Rawdon could focus on getting rid of Gen. Marion. Lord Rawdon sent orders to Col. John Tadwell Watson at Fort Watson that he was to attack Francis Marion’s militia. The time had come to get rid of the constant raiding of supplies and intercepting of communications. Col. Watson was an experienced officer. Marion would have no help from Sumter in the Waxhaws or the Continental Army in North Carolina.

Rawdon also ordered Lt. Col. Welbore Ellis Doyle with the mounted New York Volunteers to march slowly out of Camden heading east, so slowly as not to be noticed by Marion’s scouts. Doyle crossed over Lynches Creek by way of M’Callum’s Ferry, marched down Jeffers’ Creek to the Pee Dee River and headed for Snow Island. This would be a two front attack. Watson would engage Marion and force him to retreat to his base at Snow Island. Doyle would have destroyed the Snow Island camp and be heading for Kingstree to catch Marion in a crossfire or “hammer and anvil” between himself and Watson. At least that was the plan.

Watson left Fort Watson on March 5th with a great force of about 500 men: Prince of Wales Infantry, the 64th Foot Regiment commanded by Capt. Dennis Kelly, the South Carolina Rangers commanded by Capt. Samuel Harrison, Loyalist Militia led by Lt. Col. Henry Richbourg with Capt. John Brockington and the Royal Regiment of Artillery with two cannons (three-pounder fieldpieces). This would surely be enough to take care of Marion, once and for all.

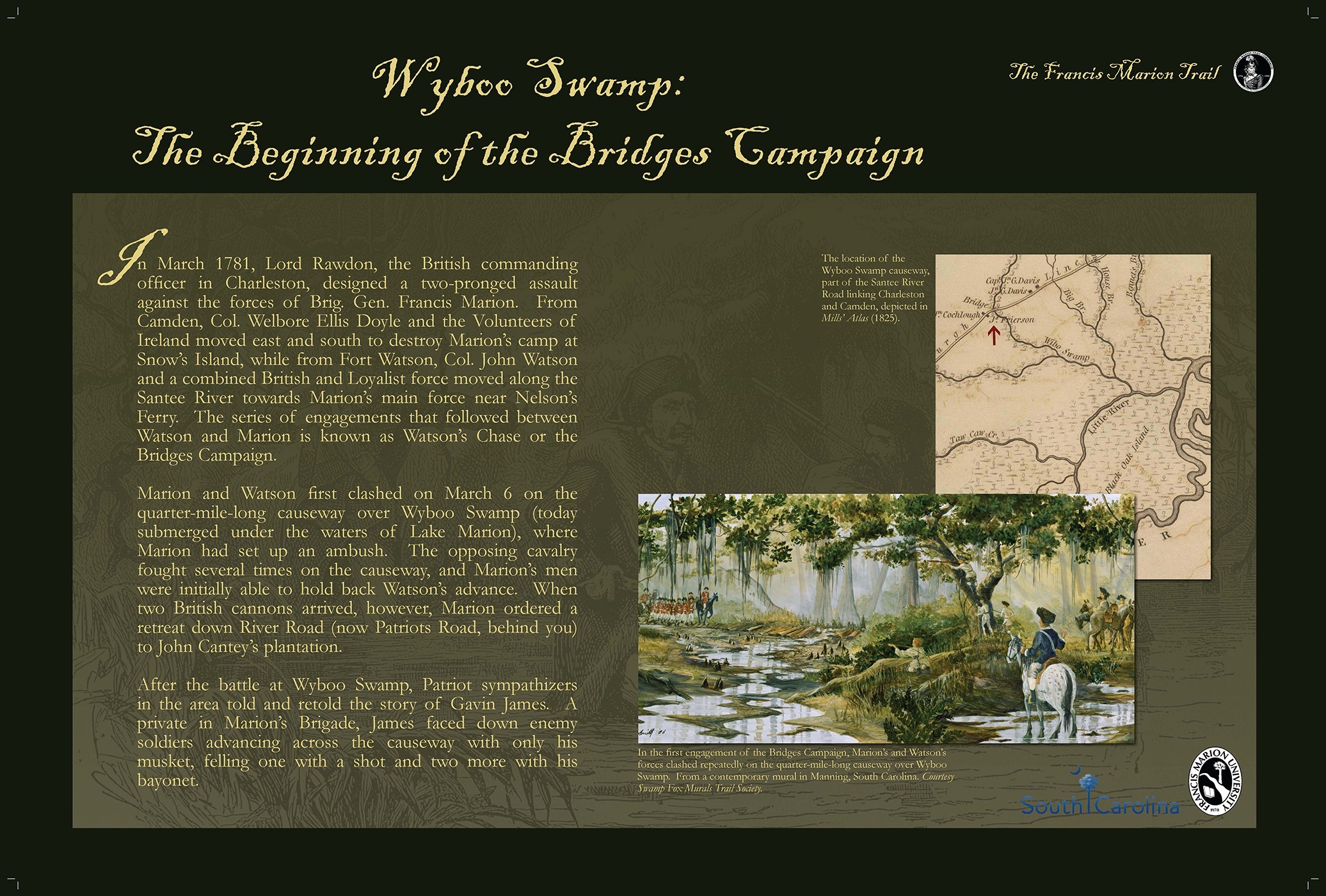

Watson’s movement was first made known to Marion on March 5th. Captain Zach Cantey spotted Watson camping near Nelson’s Ferry on the afternoon of the 5th. Marion was on his way to aid Sumter when Cantey found him just west of Murray’s Ferry. Marion had about 250 men. He knew instantly that Watson was out hunting him and his men. He immediately made for Wiboo Swamp, hid his troops and waited on Watson’s approach. Wiboo Swamp was east of Nelson’s Ferry and a perfect spot to attack Watson. Watson would be following the Santee River Road through the Wiboo Swamp. Wiboo Swamp was midway between Nelson’s and Murray’s Ferries.

As Watson came to the swamp, he cautiously entered. He knew the reputation of Marion and his tactics. On horseback he surveyed the terrain. Suddenly, Marion appeared on his horse. Col. Watson was in full uniform with all of the trappings of a British officer. Marion, wearing well worn clothes, looked every bit the woodsman.

Watson first sent forth the Loyalist cavalry commanded by Col. Henry Richbourg. As they came thundering down the road, Marion moved forward his militia cavalry commanded by Col. Peter Horry. Both sides fought hard then retreated. Marion advanced the rest of his troops and again ordered Horry to charge. Watson ordered his infantry to advance and hold their ground.

As the battle continued, Watson’s artillery blasted grapeshot at Horry’s cavalry. Horry’s forces quickly retreated. Watson sent his South Carolina Rangers, Loyalist dragoons commanded by Maj. Samuel Harrison. But now all of Marion’s militia was in retreat. A private under Horry, Gavin James, a large man on a gray horse, put himself squarely in the middle of the narrow causeway blocking the dragoons. A dragoon rode at James and was cut down by buckshot from James’ weapon. Another dragoon followed with raised saber and was speared on James bayonet. As James pulled loose his bayonet a third dragoon charged him and was also slain by the bayonet but his lifeless body held fast to the bayonet. James had to drag the body 50 yards back to Marion’s lines, still impaled on the big knife.

James had bought time for the Patriots to regroup. Marion’s men, seeing James’ courageous actions, were inspired to rejoin the fight. The Tories by now were greatly intimidated. Marion, seeing this, yelled “charge”. Capt. Daniel Conyers and Capt. John McCauley drove the Tories back across the quarter mile stretch of the causeway. Capt. Conyers killed Maj. Harrison in hand to hand combat.

It was then that Watson sent in his Prince of Wales Guards, infantry with red uniforms and helmets. These forces were too well trained and equipped for Marion’s men. Marion called his men to mount and quickly retreat. The Patriots fell back to Marion’s camp at John Cantey’s plantation.

On March 6, Marion received a letter forwarded from Lt. Col. Hugh Ervin whom he had left in charge of the Snow Island camp. The letter had been written by British Capt. Sanders in Georgetown saying that one of Marion’s men, Capt. John Postell was being held prisoner. Thus began a long exchange of letters about Capt. John Postell being taken prisoner while under a flag of truce during a prisoner exchange. This correspondence was so heated it was yet another “war” of words. Marion responded through Watson. Both sides repeated the phrase “carry on the war as usual with civilized nations” in the letter exchanges. Marion sent an armed guard to protect his flag of truce to deliver the letter to Watson. This was taken as an insult by Watson. Watson sent a letter to Marion accusing him of the same breach of conduct of which he accused Sanders. Unknown to Watson, British Cornet Thomas Merritt, who was sent to Snow Island for a prisoner exchange, was taken prisoner by Lt. Col. Hugh Ervin in retaliation. Capt. John Postell would remain in British custody until late 1782. Watson’s written response was met by Marion ordering the Patriots to shoot British and Tory pickets and sentinels whenever possible.

Watson resumed his chase of Marion on March 6. Marion slowly backed away from the Watson’s powerful force and his cannons. Watson reached Cantey’s plantation and he too camped there. By March 9 Watson had sent another letter defending Saunders’ capture of Postell. Marion ignored the letter and continued to have his men shoot Watson’s pickets. About March 13 Watson broke camp to pursue Marion. Tories were in the vanguard of Watson’s troops, followed by the British guardsmen. Marion’s relatively nimble force retreated ahead of Watson and Marion ordered his men to ride ahead and pull up the planks on the bridge at Mt. Hope Swamp.

Near the bridge Marion had his men prepare an ambush as Watson’s troops rounded a turn. Lt. Col. Hugh Horry and Capt. William McCottry had their men waiting across the ruined bridge to pick off Watson’s British and Tories. However, Watson used his cannons firing grape shot to force the Patriots back and then had his men restore the planks to the bridge and crossed it. Watson likely felt now as if his superior firepower and numbers would overwhelm Marion’s smaller but quicker militia.

Marion steadily retreated and watched Watson’s every move. The Swamp Fox wanted to keep drawing Watson away from the Kingstree area and the inhabitants who were without protection from the British. Watson had orders to pursue Marion. However, Kingstree was rife with rebel activity and Watson knew that Doyle would be on the other side of Kingstree soon. Watson kept going down the Santee Road, passing the road to Murray’s Ferry to the south as if he were heading to Georgetown. Then Watson quickly turned north and headed for Kingstree. He would have to cross Lower Bridge 12 miles away. Watson did not realize how quickly Marion’s men could make use of shortcuts through the woods and swamps to cut off his line of march. Marion’s men were woodsmen and this was their homeland. They knew the terrain well and would fight ferociously to protect Williamsburg.

The Swamp Fox had anticipated Watson’s strategy. Marion sent ahead a Kingstree Regiment of 30 men led by Major John James and a Berkeley County Regiment of 40 sharpshooters led by Capt. William McCottry to prevent Watson from crossing Lower Bridge. Marion made it to Lower Bridge and forded the river in time to see Watson approaching. McCottry’s riflemen had pulled up the planks and set fire to the eastern half of the bridge. Marion placed Capt. Thomas Potts and his Pee Dee Company to support James along the river. He placed the rest of the men further back to act as a reserve. Marion was determined to keep Watson from crossing the Black River.

Watson attempted to use a cannon loaded with grapeshot to kill Marion’s men. However, Watson was on a bluff on the western side and could not lower the cannon’s trajectory sufficiently to hit anything but upper tree trunks. Also, Marion’s men kept killing his artillerymen as soon as they became visible. The Black River was only 50 yards wide here, an easy distance for the sharpshooters but a difficult distance for the British and Tories with muskets. Watson ordered some of the infantry to advance at a shallow part of the Black River. A captain marched in the front of his men with his sword waving and was shot dead. The four men who came to carry his body off were also killed. Marion stood his ground. Kingstree was spared. Watson suffered 20 killed and several wounded, Marion 5 killed and 8 wounded.

At Lower Bridge Watson waited for nightfall and then retreated to the plantation of John Witherspoon about a mile away. He ordered his dead sunk in the Black River to hide the number he had lost. Watson told his unwilling hostess, Mrs. Witherspoon, that he had never seen such shooting. Marion sent his sharpshooters to harass Watson. One of the sharpshooters was Capt. Daniel Conyers whose fiancée, Mary Witherspoon lived on the plantation. Mary could see her fiancée circling the plantation. She dared the British to go out and face the militia. She accused them of being cowards and even struck one soldier in the face with her shoe. Conyers was desperate to get at the British encamped at the plantation. Other militia members joined Conyers and assisted in firing on the British. McCottry’s sharpshooters climbed trees and picked off many British soldiers. British Lt. George Torriano of the Guards was hit in the knee by redheaded Sgt. Archibald McDonald who was in a tree 300 yards distant. Many of Watson’s pickets were killed or wounded .Watson wrote a humble letter requesting transport for Lt. Torriano and others for medical treatment in Charles Towne. Not only did Marion grant him a written pass for the men to be unmolested in the journey, he also sent a group of his own men as escort.

Even though he could be very compassionate, Marion still wanted the British to leave the area. He allowed the shooting of pickets to continue. Finally, on March 15th, Watson moved his men to the open field of the Blakely Plantation about a half mile away. The Swamp Fox had Watson’s men harassed at every opportunity. Watson’s men could not forage or rest with an enemy that never slept. The British and their allies stayed at Blakely’s for almost two weeks. Was he waiting on word from Lt. Col. Doyle? Did the weather play a role in the decision to stay so long at Blakely’s?

By March 28th Watson finally decided that Doyle was not going to join him. Watson had received no message from Doyle and Watson’s messengers could not get past Marion’s men. Low on supplies, Watson decided to make a break for Georgetown. He marched double-time eastward down the Black River Road for seven miles to Ox Swamp only to find destroyed bridges and trees felled in the road.

Marion had ordered his men to make the road impassable. Watson had to make a decision to flee or fight. He suddenly turned his men to the right and quickly headed for the Santee River Road fifteen miles away. Anticipating this move, Marion had concealed his men behind trees and thick brush heading south. Watson moved at a fast pace through the swamps and pine land forests with Marion’s men shooting all along the way. The British sometimes stopped and turned briefly to shoot back but then resumed their harried march southward. Occasionally, Watson used his artillery to fire grapeshot at his unseen enemy.

Once Watson got to the Santee River Road he headed eastward for the Sampit Bridge. The men and horses were in a mad dash down the road toward Georgetown with Marion behind them every step of the way to Sampit Bridge. Marion sent some men ahead to harass the British and their Tory allies.

Peter Horry sent another group of riflemen led by Lt. John Scott ahead of the British to pull up the planks on the Sampit Bridge. Horry and a dozen men waited on the Georgetown side of the bridge. The approaching Watson saw the pyramidal shape of the Sampit Bridge and sent some of the Light Infantry ahead to see if the planks were intact. Watson’s men saw that the planks had been removed and Marion’s men were waiting on the Georgetown side. Watson later wrote that Scott’s men began shooting at the infantry (British and Tories) on the bridge just as Marion approached. Watson fought Marion with the 64th Regiment while the Light Infantry engaged Scott’s men and repaired the bridge. Lt. Scott retreated thinking he was being outflanked by the British. Scott was later admonished by Horry for retreating as he could have inflicted much damage to Watson.

Marion mounted a fierce rear guard action as the British retreated across the Sampit River. As the intense fighting continued, Watson went back to rally his men. His horse was killed beneath him. Watson’s black servant fired a fowling piece giving Watson time to quickly mount another horse. He ordered artillery to open fire on the Patriots with grapeshot. Marion and his men wisely elected to fall back out of range of the heavy metal balls. This gave Watson enough time to retrieve his wounded and cross the Sampit. He left his dead at the river and headed for Georgetown with two wagons full of injured soldiers. Watson had twenty men killed and thirty-eight wounded. Marion had one killed. The whole campaign left the British and Tories with over forty dead and a great many more wounded while Marion’s losses were twelve dead. Watson camped in the vicinity of Georgetown and complained that Marion and his men “did not sleep and fight as gentlemen but like savages….waylaying and popping at him from behind every tree….”

Yet again Marion had escaped capture and saved the inhabitants of the Williamsburg area of South Carolina. He and his men had protected the citizens and struck a blow against the British. This great victory would not be celebrated for long. Soon, news came to Marion that while he was chasing Watson, his famous hideout on Snow Island had been attacked by Lt. Col. John Doyle. A traitor had led the British to the camp. In his zeal to defeat Watson Marion had neglected to get reconnaissance of other British movements in the area. Marion abandoned the battered Watson and rushed to Snow Island to intercept Doyle.

General Nathanael Greene, Commanding Officer of the Southern Theatre, would later write on April 24, 1781 in a letter to General Francis Marion:

“History affords no instance wherein an officer has kept possession of a country under so many disadvantages as you have; surrounded on every side with a superior force; hunted from every quarter with veteran troops, you have found means to elude all their attempts, and to keep alive the expiring hopes of an oppressed Militia, when all succor seemed to be cut off. To fight the enemy bravely with a prospect of victory is nothing; but to fight with intrepidity under the constant impression of defeat, and inspire irregular troops to do it, is a talent peculiar to yourself. Nothing will give me greater pleasure, than to do justice to your merit, and I shall miss no opportunity of declaring to Congress, the Commander-in-chief of the American Army, and to the world in general, the great sense I have of your merit and services.”

STOP 3: Halfway Swamp

Driving Directions:

When ready to proceed to Halfway Swamp, simply retrace your steps 1.1 miles back up State Road 410/ Patriot Road to the intersection with Hwy. 260 and turn left onto Hwy. 260. Proceed back up Hwy. 260 for 10.8 miles to the intersection with Hwy. 301 and turn left onto Hwy. 301. Go about 10.2 miles to Summerton. Where Hwy. 301 makes a hard left turn in Summerton, continue straight ahead onto Hwy. 26 which is 11.3 miles from the beginning of Hwy. 26 in Summerton to Old River Road in Rimini. Turn left on Old River Road in Rimini and go 1.2 miles to the interpretive sign for Halfway Swamp on the right side of the road at the intersection of Old River Road and the dirt road leading to Elliott’s Landing and Campground (large sign marks this intersection and pull-off).

In Pursuit of a Brother to Kill Him

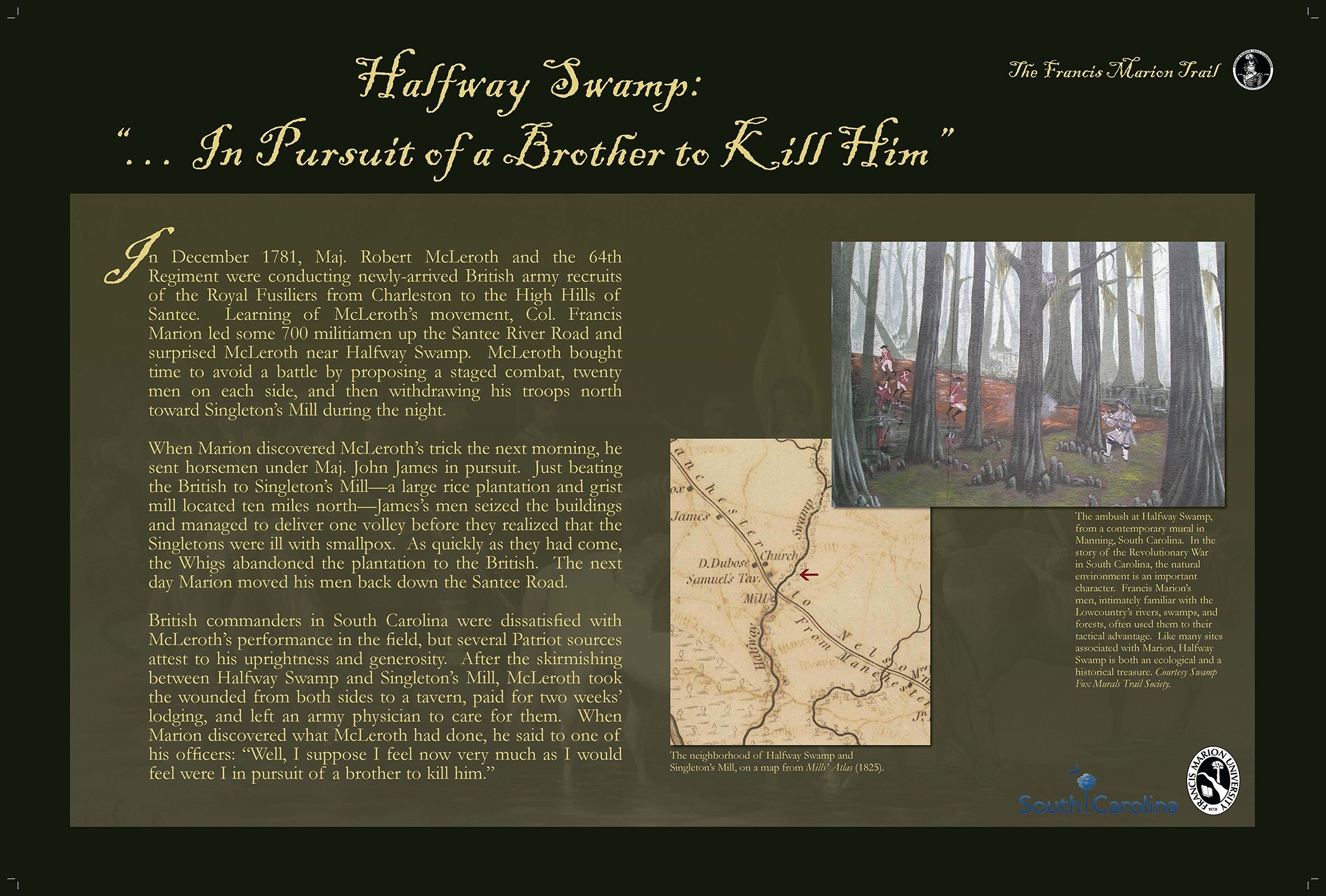

In December 1781, Maj. Robert McLeroth and the 64th Regiment were conducting newly-arrived British army recruits of the Royal Fusiliers from Charleston to the High Hills of Santee. Learning of McLeroth’s movement, Col. Francis Marion led some 700 militiamen up the Santee River Road and surprised McLeroth near Halfway Swamp. McLeroth bought time to avoid a battle by proposing a staged combat, twenty men on each side, and then withdrawing his troops north toward Singleton’s Mill during the night.

When Marion discovered McLeroth’s trick the next morning, he sent horsemen in pursuit. Just beating the British to Singleton’s Mill—Matthew Singleton’s large rice plantation and grist mill located ten miles north—Maj. John James’s men seized the buildings and managed to deliver one volley before they realized that the Singletons were ill with smallpox. As quickly as they had come, the Whigs abandoned the plantation to the British. The next day Marion moved his men back down the Santee Road.

British commanders in South Carolina were dissatisfied with McLeroth’s performance in the field, but several Patriot sources attest to his uprightness and generosity. After the skirmishing between Halfway Swamp and Singleton’s Mill, McLeroth took the wounded from both sides to a tavern, paid for two weeks’ lodging, and left an army physician to care for them. When Marion discovered what McLeroth had done, he said to one of his officers: “Well, I suppose I feel now very much as I would feel were I in pursuit of a brother to kill him.”

- The neighborhood of Halfway Swamp and Singleton’s Mill, on a map from Mills’ Atlas (1825). [Map.]

- The ambush at Halfway Swamp, from a contemporary mural in Manning, South Carolina. In the story of the Revolutionary War in South Carolina, the natural environment is an important character. Francis Marion’s men, intimately familiar with the Lowcountry’s rivers, swamps, and forests, often used them to their tactical advantage. Halfway Swamp is both an ecological and a historical treasure. [Halfway Swamp mural.]

STOP 4: Fort Watson

Driving Directions:

Leave Halfway Swamp and proceed on Old River Road for 8.4 miles until you come to a “T” intersection with Liberty Hill Road and turn right. Go 1.0 miles and merge right with Hwy. 301/15. Proceed another 3.7 miles until you reach the intersection with Fort Watson Road (on your right) which leads to the Santee Wildlife Refuge. Good signs mark this “T” intersection. Across from this intersection on the left side of Hwy. 301 is a pull-off and the interpretive sign for the Siege of Fort Watson. You may then wish to go back a few yards and follow Fort Watson Road into the Santee Wildlife Refuge. The large (40 foot high) American Indian mound on which the fort was built may be viewed at the end of this road which is roughly 2 miles from the intersection with Hwy. 301. You will pass the Santee Wildlife Visitor’s Center on the way to the mound. This road is generally open to the public during daylight hours. Upon exiting Fort Watson Road onto Hwy. 301/15 bear to the right to access Interstate 95 about 1 mile distant.

Disrupting British Supply Lines

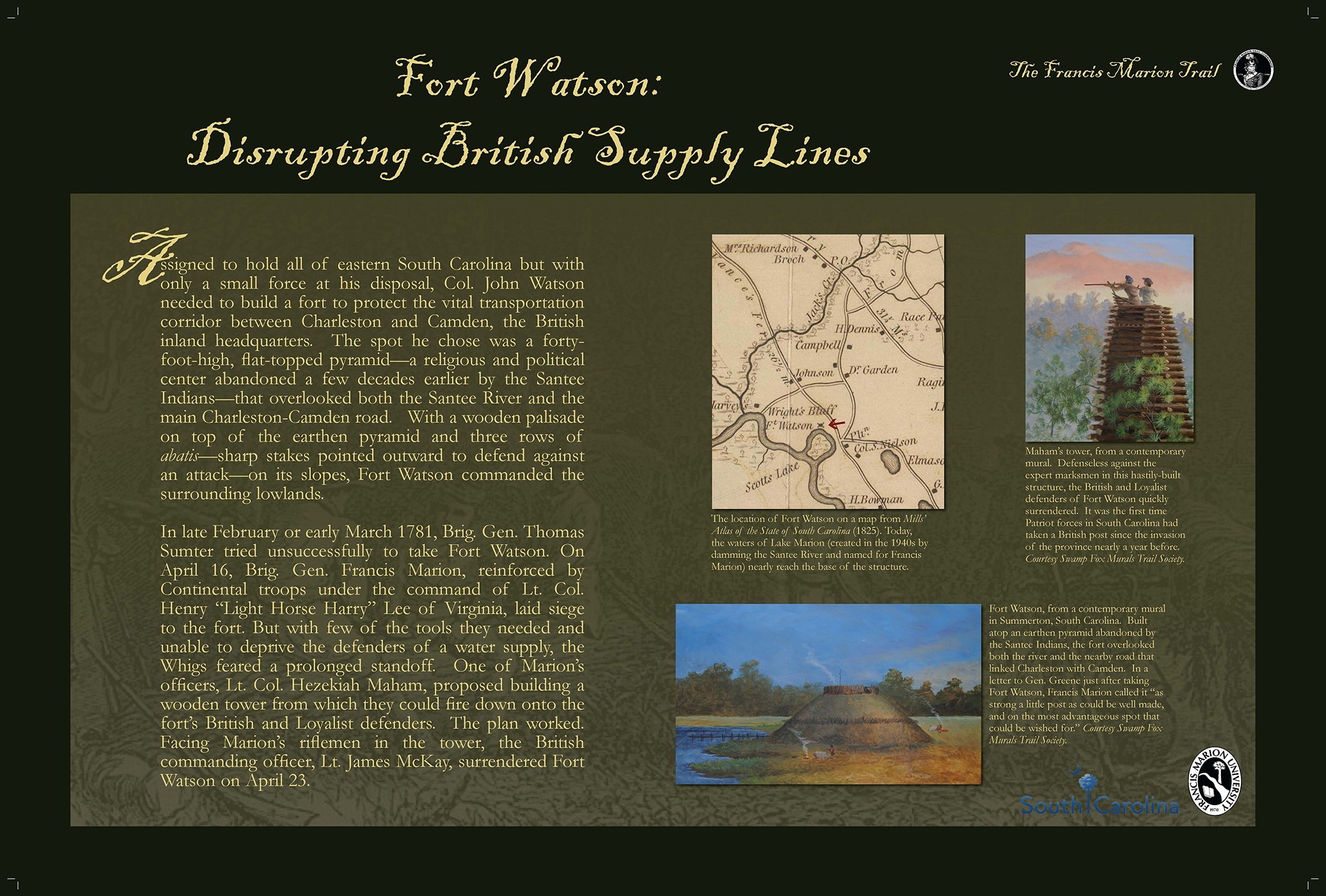

Assigned to hold all of eastern South Carolina but with only a small force at his disposal, Col. John Watson needed a fort to protect the vital transportation corridor between Charleston and Camden, the British inland headquarters. The spot he chose was a forty-foot-high, flat-topped pyramid—a religious and political center abandoned a few decades earlier by the Santee Indians—that overlooked both the Santee River and the main Charleston-Camden road. With a wooden palisade on top of the earthen pyramid and three rows of abatis—sharp stakes pointed outward to defend against an attack—on its slopes, Fort Watson commanded the surrounding lowlands.

In February 1781, Gen. Thomas Sumter tried unsuccessfully to take Fort Watson by storm. Two months later, Brig. Gen. Francis Marion, reinforced by Continental troops under the command of Lt. Col. Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee, laid siege to the fort on August 16, 1781. But with few of the tools they needed and unable to deprive the defenders of a water supply, the Whigs feared a prolonged standoff. One of Marion’s officers, Lt. Col. Hezekiah Maham, proposed building a wooden tower from which they could fire down onto the fort’s British and Loyalist defenders. The plan worked. Facing Marion’s riflemen in the tower, the British commanding officer, Lt. James McKay, surrendered Fort Watson on April 23.

- The location of Fort Watson on a map from Mills’ Atlas of the State of South Carolina (1825). Today, the waters of Lake Marion (named for Francis Marion), created in the 1930s by damming the Santee River, nearly reach the base of the structure. [Map.]

- Fort Watson, from a contemporary mural in Summerton, South Carolina. Built atop an earthen pyramid abandoned by the Santee Indians, the fort overlooked both the river and the nearby road that linked Charleston with Camden. In a letter to Gen. Greene just after taking Fort Watson, Francis Marion called it “as strong a little post as could be well made, and on the most advantageous spot that could be wished for.” [Fort Watson]

- Maham’s tower, from a contemporary mural. Defenseless against the expert marksmen in this hastily-built structure, the British and Loyalist defenders of Fort Watson quickly surrendered. It was the first time Patriot forces in South Carolina had taken a British post since the invasion of the province nearly a year before. [Tower mural.]